Film:

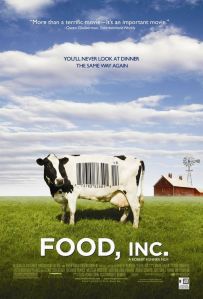

Food, Inc. 2008

Synopsis (from Netflix):

Drawing on Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation and Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, director Robert Kenner’s documentary explores the food industry’s detrimental effects on our health and environment. Kenner spotlights the men and women who are working to reform an industry rife with monopolies, questionable interpretations of laws and subsidies, political ties and rising rates of E. coli outbreaks.

My Thoughts:

First I would like to thank the reader who voted in the poll and suggested this film. Secondly I would like to advocate that *everyone* watch this. If you haven’t seen it, it’s on Netflix Instant. Watch it now. Ok, on with the post.

Robert Kenner begins this documentary saying that the food industry has changed more in the last 50 years than in the previous 10,000 and that his hope in creating this documentary is to “pull the veil back” and show people how they are really eating and where there food had come from.

Remove the veil from their eyes, and enlighten their hearts with the light of guidance. —‘Abdu’l-Bahá

This is a veil that I myself have been pulling back slowly but surely over this past decade, and it is quite shocking and disheartening. Our food industry has become so industrialized and so far removed from those consuming the food that it’s interests no longer match those of the consumers.

In this documentary there were several interviews with farmers and one shared some statements that I thought were pretty profound that I would like to share with you. First:

“Industrial food is not honest food. It is not produced honestly. It is not priced honestly. There is nothing honest about industrial food”

As we know truthfulness is the foundation of all virtue, and without it there cannot be justice. The industrial food system is so highly subsidized that the food can be sold below cost. This puts pressure on both independent farmers, as well as farmers outside of the US who cannot compete because they don’t have these subsidies and can’t sell below cost. Also, the cost to the environment is not factored in to these industrialized methods which are not as ecologically sound. E Coli was not a problem before this system. These hidden costs are dishonest. The food industry also uses undocumented workers who they can pay cheaply, and treat poorly. It is the workers who are punished if caught even if the industry purposely goes to Mexico to recruit them. Chickens have been manipulated to grow three times as fast but in doing so their bones can’t support their weight so they can barely stand. This is also unjust. How can we treat people and animals so cruelly? As the farmer so aptly put it:

“A culture that just views a pig as a set of protoplasmic structures to be manipulated will probably view other people in its community, and the community of nations with the same controlling type mentality”

Or if you prefer Holy Writings:

Burden not an animal with more than it can bear. We, truly, have prohibited such treatment through a most binding interdiction in the Book. Be ye the embodiments of justice and fairness amidst all creation. ~Bahá’u’lláh

Eating food is something we do everyday, three times a day. How can we do so with integrity? With justice? Over 100 years ago Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle and that changed our food industry for a time. People demanded better regulation. But that system broke down as the food industry became more powerful. Also, the cheaply subsidized food is not the healthiest food, but instead commodity crops, and has led to the epidemic of obesity. At the end of the documentary the filmmakers list several suggestions as to how we can work together as a society and as individuals within this society to combat this problem. Here are three:

You can vote to change this system. Three times a day.

Buy from companies that treat workers, animals, and the environment with respect.

If you say grace, ask for food that will keep us, and the planet, healthy.

It is up to us. We can be the change we want to see in the world. Those who can afford to, to vote with our wallets and support ethically grown food. Doing so is better for us, for our health, for the world, and for peace.

My friends have also posted a wonderful blog on the topic of ethical eating. Check it out here.